Thursday, March 27, 2008

Other than myself/my other self (Trinh T. Minh-ha)

The author begins her by writing about language and it is not 'It' that travels but the 'I' that carries a few fragments of it as we travel. We take bits and pieces of our pasts and move forward in forming our own identity. She explains that language "is the site of return and the site of change" in that it changes its rules as it goes. I see language as part of the self. I often feel challenged and conflicted with my identity as a Francophone. I cherish my mother tongue very dearly however it has become increasingly difficult to preserve it as I move around the country and encounter new people who do not share this same language. This is especially true of my current situation here in Newfoundland. I feel as though I have left part of my language back home, even back in Ottawa and have only taken certain pieces of this identity with me. I feel as though I have done this because I fear not being understood. I also feel as though what I have taken with me and use (not very often) is not personal but like what Minh-na writes of exiled writers= choice of tales no longer belong to them as individuals. I speak not for myself but for my 'people'. (Now I realize that this article is speaking of 'others' in terms of races and ethnicities and that my Francophone identity perhaps does not compare but it is somewhat along the same lines of what she is describing.)When I go back to the origin of my language, I feel like a stranger because I have not spoken it for a significant amount of time and have not tried hard enough to preserve my individual identity. I hear it in my dialect and as I search for my words because I can only think of them in English.

Minh-na also argues that as you come to love your new ‘home’, it is thus implied, you will immediately be sent back to your old 'home' where you are bound to undergo again another form of estrangement. (13) So she is saying that once you become comfortable in new surrounding whatever that may be, you can then be your true self once again. However it is difficult to go back to your old self in a new setting I think. Although you may value your identity and your language for example, part of you feels displaced and misunderstood. This often results in performing a variation of your true identity to ‘fit in’. Once you become fully comfortable, it risky to bring forth your true identity. Isn’t it? A trivial example of this is a personal intimate relationship. When you first meet or start a new relationship, very often we do not feel at ease being ourselves in this new and uncertain environment. Once the relationship is more stable and you feel "at home", bits and pieces of your original self begin to show. This is not always a positive thing as it can result in rejection from the partner. So in relation to what the author is discussing, those who are exiled, the experience (…) is never simply binary (…), [It is] hard to be stranger and hard to stop being one.

Finally, I want to bring up the significance of her idea that by assimilating or conforming the self can get lost. This is something I’ve been bringing up all throughout the semester in my posts during the semester. I’ve been working through the idea of knowing who I am. In writing these pieces I have come to the realization that in the past I have often worried too much about what others thought and tried to conform to what was/is considered ‘normal’ cultural practices. But as I think I’ve mentioned before, in assimilating myself, I felt as though parts of the ‘real me’ had faded away. It was until I reminded myself of my true identity that I started to accept the fact that I was not going to conform to ways of dressing, or speaking or consuming for example. However, and I want to end on this, as Minh-na reminds us, "to strive for likeness to the original - which is ultimately an impossible task - is to forget that for something to live on, it has to be transformed. So I have learned that I do not want to conform but, in order for my true ‘self’ to live on, it has to change in the process. I cannot be who I was 10 years ago for example. This means embracing my new surrounding and taking bits and pieces that will not completely disrupt my identity but make only make it richer.

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

On Not Speaking Chinese. Postmodern Ethnicity and the Politics of Diaspora (Ien Ang)

The first idea that I wanted to point out was her brief discussion of Stuart Hall’s politics of self-representation and how it is not an establishment of an identity per se but a strategy to open up avenues for new speaking trajectories. For some reason it made me think of my partner who is Greek. The two of us often use our ‘labels’ to define the differences between us; my partner is Greek and I’m French Canadian. He also uses his Greek identity as a way to justify the need to go to Greece to supposedly to find his roots. The problem with this is that he is only Greek by origin and by name. He does not speak the language nor does his family (except for his grandfather) and he does not adhere to any practices or traditions. The only time that they have demonstrated this ‘identity’ to me was the very first time I visited them in their hometown for Easter. At Easter dinner they followed an old Greek tradition of a game of breaking eggs. My partner was shocked that his mother had prepared it and said: "of course because you’re here, we decide to actually be Greek. We’ve never done this before." I'm trying to think of what this story I have just recall means in terms of politics of self-representation. If it's not an establishment of a specific identity, what exactly is it? Is he not satisfied or conflicted by his too stable and uneventful identity as a Canadian? Why does he choose to sometimes really promote his Greek identity and then other times, make it seem like it's not of significant importance.

The second point I found significant in this article was when she quotes from the memoir of Ruth Ho which spoke to the contradictions and complexities in subject positioning. Ho says: "Are the descendants of German, Norwegian and Swedish emigrants to the USA, for instance, expected to know German, Norwegian and Swedish?"(556) I immediately thought of it as a double standard and that by not having such expectations of European emigrants, we are expecting more ‘authenticity out of those who are ‘visible’ minorities. I agree with Ang when she says that it this double standard is "an expression of the desire to keep Western culture white". I also think that the idea the politics of diaspora trying to keep non-white or non-Western elements from entering our culture is somewhat true. It is interesting that we are perplexed when a ‘visible’ minority does not speak their language of origin or practice cultural traditions and accuse them of being inauthentic but yet we do not want that authenticity to infiltrate itself into our ‘white culture.’

Tuesday, March 25, 2008

Cultural Identity and Diaspora (Stuart Hall)

To come back to Hall’s discussion, when speaking of this similar yet different identity he states that identity is something, that it has a history but is not fixed, that difference matters. He also notes that language depends on difference as Derrida spoke of. So identity can be different and differ basically. This theory helps disturb the "classical economy of language and representation" and to Hall it helps them (Caribbeans) to "rethink the positioning and repositioning of Caribbean cultural identities in relation to at least three ‘presences’."

2) Presence Europeene which is the site of colonialist. This presence includes issues of power and how the Europeans have positioned black in visual representation in dominant discourse. When I took Women Racism and Power in my undergrad, I remember our professor bringing in products from the supermarket such as sauces and couscous boxes. I wasn’t too sure why at first but she made us realize the power that we (dominant) have in representing the "other" in visual images. The products she brought were from the President’s Choice line called Memories of... As we can tell from the images below, those who have designed the packaging have chosen to use a woman who appears to be of Asian descent to represent memories of Shanghai and then we find a man on a camel to represent Kashmir. Not only do we the dominant have the power to represent the other’s identity through these constructed images but we are putting them out there to be consumed. If you put this sauce on your food, you will have experienced Shanghai for example. Just as I am writing this, I realize how absurd it is.

Monday, March 24, 2008

Things to do with Shopping Centres (Meghan Morris)

Morris wants to discuss issues for feminist criticism that emerge from a study she's doing of the management of change in certain ‘sites’ of cultural production involving practices regularly, if by no means exclusively, carried out by women. (11) So this seems like one of the main focus of her article, amongt what I think is "too many" otheres. I am unsure about how she implies that women do all the shopping and what is involved with it. I am not denying that women do not practice generally but it is excluding the increasing number of men who perform those tasks. What does that say about normatised gender roles?

The project which she discusses is looking a differences in shopping centers to see how particular centers "produce and maintain (…) ‘a unique sense of place’—in other terms, a myth of identity.

Exploring common sensations, perceptions, and emotional states aroused by them (…) and on the other hand, battling against those perceptions and states in order to make a place from which to speak other than that of the fascinated describer. (14) By analyzing it from a feminist perspective she claims that we can see how it allows for the possibility of rejecting, what we see and refusing to take it as given.

What is especially significant and seen as a contribution of this article, is the fact that she acknowledges that her article is not meant for ‘ordinary’ women but more for academics, students etc…but that this not mean that it condescends women shoppers either. She raises the issue of theory being in the every day. Theory doesn’t always imply academia for as she says, those who conceive of shopping centers also do theory as they theorize the conception of the shopping center on consumers (in this case, women).

Since I had a difficult time understanding how this article was meant to speak of sites of remembrance, I want to work with this idea of theory and who and why people do it. I remember talking about this in another class last semester and thought it was quite interesting since theory is something I seem to struggle with. I think we were speaking of bell hooks’ idea of how children make the best theorists because they have not yet been educated and exposed to our daily social routines and norms. What was key for me in this article was the discussion on how we, ‘ordinary people’ as Morris would say, practice theory without ever knowing it or labeling it as such. I often found it hard to theorize when I had to do it, but in reality we do it in our every day lives without even realizing it. For example, we are constantly theorizing our memories. We remember them differently and question what we really observed or experienced. By doing this we are deconstructing and reconstructing our memories, sometimes to make us feel better but other times to make sense of what is happening in our lives at the present time. If you think about it, it is actually a very postmodern thing (i.e. Derrida) but only this is done in our personal lives and not in literary texts. I have come to realize that some of us keep personal journals and oftentimes (I know I do) we go through them years later and analyze and ‘theorize’ how we handled certain situations and how we now make sense of it or how we would of handled it better. So we should be encouraged to use ‘theory’ in whichever way we understand it to inform our practice and work towards new understandings of our lived experiences.

Monday, March 17, 2008

"Remembering Well": Sexual Practice as a Practice of Remembering (Kate Bride)

At first, I was not sure how the idea of public gay sex could be understood as a practice of remembering those who have died from AIDS. I fell into the all too easy and "normative" assumption that it would be disrespectful to engage in sexual activity at a site of rememberance. As I went further into the article, reading about "appropriate displays of rememberance" and curing "innapropriate behavior", I began to think about how our behaviors are overly dictated by what is deemed "normal". This is not a new insight but it was good to revisit the idea. When I read "normative notions of private and public behaviors", I asked myself the following questions: What are considered normal private and public behaviors and, with the issue of public gay sex, would it be considered as deviant is it was public heterosexual sex? Is it deemed innapropriate behavior because it is in public - do we feel as threatened by the behaviors when they are out of sight?

I found interesting that "the CAP initiative- to "clean up" innapropriate behaviors, to force out 'undesirable'- is just one of the ways that discourses about public space not only regulate particular behavior but also, work to 'erase differences and to limit the forms of expression we have available to us'."(Bride, 52) We too often stay embedded in sameness or try to conform to be the same. Many of 'us' are afraid of being different, often by fear of not being socially accepted. We are often measuring ourselves "in relation to" something. We find ourselves judging those deemed out of the norm, especially those who are strangers to us - it has been made easy to do so, "normal" even. When I lived in my hometown and even in the first few years in a large city, I found myself worrying about being different, about not fitting in and judging those who acted against what was deemed normal. I probably still do it from time to time but I have come to embrace difference moreso than being like everyone else.

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

Portraits of Grief: Telling Details and the Testimony of Trauma (Nancy K. Miller)

Source:http://images.google.ca/imgres?imgurl=https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIoz94tjkY7omw0ypizON8nltTyKMtwFlhziBV2Z6SrLIyp-Wo_S9QBj9tGqtgvO8L_5t_H3ZTd9U8cKw3HW78khtFZIjtBOPMGzcASvN5125WO5h4hyphenhyphenlp1-YGQ0gSgZt_nfagFk269ui_/s400/pog_430_749.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.timreilly.com/2001/11/new-york-times-portraits-of-grief.html&h=400&w=230&sz=24&hl=en&start=4&tbnid=2qFhrM4ZkkDmVM:&tbnh=124&tbnw=71&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dportraits%2Bof%2Bgrief%26gbv%3D2%26hl%3Den

In a sense, as Miller explains, we focus on the small happy things to deal with the BIG loss that comes with death because it is not as difficult to cope if the remembrance is done is small steps and fragments.: In the case of 9/11 it was fitting to remember the small details as a way of situating the loss within a bigger loss. The nation was in mourning and feeling a great loss. In choosing to remember the individuals and the telling details of their lives, it without a doubt must have make the grieving process easier.

Tuesday, March 11, 2008

Collecting Loss (Carol Mavor)

She seems to be saying that the way we narrate or interpret a photograph reconstructs our lives : "living does not easily organise itself into a continuous narrative. It is only after we have lived through cycles of our lives, in recollection, in photographs, that a narrative comes through."(115) This seems very plausible as many photographs in our possession are ones that we do not hold a current memory of because we were too young at the time. In viewing and going over photographs and memorabilia we interpret and assign a narrative to them on our own or through what has been recounted to us by those who took the picture or were there at the time. By editing family albums to represent certain times and emotions we construct our history and truths.. Sort of like a "general covering over that perpetuates dominant familial myths and ideologies" (we mask pain and reality by "posing’) This is what I wrote about in my previous post.

The feeling I got when reading her work was that a family album to her portrays sadness and loss which I think is kind of depressing. As I’ve mentioned in my previous post, I love pictures and albums ( I have them every where in my house), but to me, it is a way of remembering good times or perhaps not so good and reflecting. I do not feel like I’ve lost something by looking at moments’ passed and gone. I’d rather think of it as a good time that was had and now I’ve moved on, but it will always be part of my memory. "Every photograph is a record of a moment forever lost - snapped up by the camera and mythically presented as evermore."(119)

Mavor also sees tearing or cutting a photograph as a violent act which I am unsure about. I can see it as true in the sense of if it being out of spite; for example tearing up a picture of an old partner at the end of a relationship. These ravished photographs indicate loss and untold stories. But in any photograph I think lies an untold story; it's a moment in time that is fixed on a piece of paper.

Family, Education, Photography (Judith Williamson)

She first speaks of the family as the backbone of the State in the sense that the ideology maintains the status quo and, at the same time has economic value to capitalism. What is interesting is that the state has promoted (in opposition to latter ideology) images of the family as independent but at the same time, they are all the same (cuts across power, race, class etc...) Photographs are the most popular of these images as they are "means through which ideological representations are produced; like the family, it is an economic institution with its own structures and ideology."(334)

Williamson introduces three types of production relationships in the area of photography and the family:

Photography has developed contemporary image of family by making them look alike despite class and race differences for example. We assume because they are dressed in similar styles of clothing and are photographed in a certain context or place that they are equals. That race, power, sex and class differences are non existent because they photograph does not depict it. We do not interrogate pass the image. It is to have great power to be able to present images in such ways.

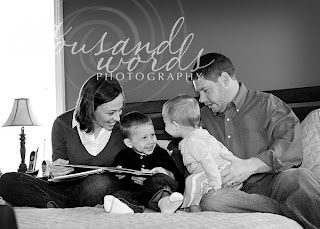

Family photographs are also now meant to symbolise ‘fun’ whether through the image itself or through the process of taking the informal pictures. "internal states of constant delight are to be revealed on film. Fun not only be had, it must be seen to have been had."(339) They are meant to symbolise fun but sometimes, especially in more formal type photography we have to pretend like we’re having fun for the photograph to ‘turn out’. I remember as a child, my family was not that keen on family portraits but the one year that my mother decided that we ‘needed’ to have a decent family picture taken by a professional, all 3 children and my father dreaded the experience of having to put on matching clothes (because we dress like this every day!?) and ‘having to’ smile for the annoying photographer. Notice how formal pictures and sometimes the informal ones, make you pull out that smile that is obviously forced? Well, that year, the family photos were terrible. Eyes closed, people slouching, fake smiles, no smiles. My mother was upset because we did not ‘look’ like a happy normal family. I didn’t understand at the time but I can see that she might have been comparing our photos to those who looked like they had had fun during the process of production.

Would we ever see this in a family album? I know this is obviously a dramatization but it represents possible family scenarios.

Thursday, February 21, 2008

Black Barbie and the Deep Play of Difference

I played with Barbies probably until the age of 10 – 11 or so and up until taking a Women’s Studies course where Barbie was deconstructed and some saying that they would never buy them for their daughters one day I had never really put much thought into their significance. I absolutely loved playing with them, all 15 or so of them which are all now stuffed in a box in my childhood bedroom. I had all different kinds of them, not to mention the quintuplet babies and one Ken doll. My father had built this massive house for all of them as well. I did not think anything of it back then obviously but I did not have one single non-white doll. All had the long blond hair, fair skin and fancy clothes. I think the only one that sort of stood out from the rest was my Gem and the Misfits doll which wasn’t really a Barbie. I do not think I ever desired a Black Barbie because it didn’t occur to me that I needed to have one. I had seen them on store shelves and Sears catalog but I did not identify with them. When I read « Now little girls of varied backgrounds can relate directly to Barbie »(109) – new ethnic Barbies for self-identification and positive play and allowing girls from all over the world to live out their fantasies in spite of a real world that may seem too big. – Living through a doll – implying that because they are of a certain race or class or look they will never be able to achieve what Barbie has or looks like. I remember struggling with White Barbie even though I had such a big number and types. I had greasy long light brown hair, had fair skin covered in freckles, chubby cheeks and legs and grayish blue eyes and wearing my sister’s hand me downs or clearance sale clothes from the local K-Mart. All I remember is just desperately wanting to look like her because this is what I thought was beautiful. Skinny, long blond hair, perfect blue eyes, legs as long as I had ever seen and beautiful shiny clothes. I never for one second thought that this was manufactured and completely unrealistic.

So this article speaks of difference and identifying the self with this so called different « ethnic » Barbie. Mattel attempted to produce multicultural meaning and market ethnic diversity…does so by mass-marketing the discursively familiar – by reproducing stereotyped and visible signs of racial and ethnic difference. Just like I found that I couldn’t identify completely with White Barbie, how is it even possible for an addition of dark tint to the plastic mold appeal to little Black girls? As duCill argues Mattel is making the Other at once different and the same and what she calls the idea of a melting pot pluralism which simply « melts down and adds on a reconstituted other without transforming the established social order, without changing the mold. » Idea of multiculturalism without valuing difference- Mattel did it and we do it in our own everyday practices. When I was working full time, I had the role of assisting the event planner and remember having to help organize Multicultural Day and also the opening ceremony for Aboriginal Awareness Week. For both events, a variety of « cultural » foods were to be provided for taste but we never stopped and explain the significance or origins but just said eat this, it’s different. It’s like we think well I ate this, it was good and I participated in promoting multiculturalism.

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Second-Hand Dresses and the Role of the Ragmarket (Angela McRobbie)

The main argument of the chapter is that second hand style should be analysed within the broader context of postwar subcultural theory. So to understand this I had to look up the definition of 'subcultural theory' first. Wikipedia defines it as a "distinctive culture within a culture, so its norms and values differ from the majority culture but do not necessarily represent a culture deemed deviant by the majority."(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subcultural_theory)

Notice the reactions of those around you if a woman, perhaps yourself, says that they do not enjoy shopping. The immediate reaction is that of shock and lack of understanding why and how a woman does not have that "natural" shopping instinct that is too often labelled onto women. Or look at it differently and imagine the reaction towards a man saying that he enjoys shopping. What is the immediate reaction to that? O.k. I seem to have gone way off topic now but this would make for really interesting research I think. To look at how dominant discourses have dictated who should what kind of shopping and the reasons why.

Notice the reactions of those around you if a woman, perhaps yourself, says that they do not enjoy shopping. The immediate reaction is that of shock and lack of understanding why and how a woman does not have that "natural" shopping instinct that is too often labelled onto women. Or look at it differently and imagine the reaction towards a man saying that he enjoys shopping. What is the immediate reaction to that? O.k. I seem to have gone way off topic now but this would make for really interesting research I think. To look at how dominant discourses have dictated who should what kind of shopping and the reasons why.To come back to the ideas of the article, the author analyses the 60s hippy fashion as a statement against materialism , « a casual disregard for obvious signs of wealth, and a disdain for the "colour of money" » (137) Stuart Hall’s analysis of it was that this was an «identification with the poor » and sort of a disavowal of conventionality of the middle-class. I never actually saw it in this way, I always thought it was just forming and/or portraying a different identity, trying to be a rebel. I never thought of it in terms of poverty and the power to create such an image. She does argue that this behaviour or way of dressing is an unconscious identity formation and is not meant to be hurtful to those who « need » to shop the ragmarkets. This introduces the question she raises through Angela Carter’s work, on whether those who rummage in those « jumble » sales make light of those who search in need and not through choice. « Does the image of the middle-class girl "slumming it" in rags and ribbons merely highlight social class differences? » Does it bring the idea that middle-class individuals have the power to pull off that look, the power to move through various social classes without feeling the repercussions or experiencing the reality of it. This is what she calls the idea of being able to «afford » to look back and play around with idea of being poor (138)

Although she points out that this is done unintentionnaly, I started thinking about my childhood clothing. My family was lower middle-class and seeing as I was the youngest, I inheritated my sister’s hand me downs which were 5 years old and only got some new clothes for the new school season. Even then, it was from the cheepest place in town which was K-Mart at the time. I remember being envious of those who had new clothes all the time, especially those with brand names(especially in high school). I wonder what my reaction would have been if I knew that people were purposely wearing hand me downs or shopping at second hand clothing stores even though they had money for the nice things.

McRobbie also mentions that 1960s hippy clothing was a reminder of stigma of poverty, the shame of ill-fitting clothing but for the hippies it was not to create an element of shock rather than to promote a come back to nature, and authentic fabrics and a protest against man made synthetics. There is and was more value in a piece of clothing that was made through and through by one individual. It was also seen (as I still see it today) as a political action in the sense that it was/is creating an alternative society. Today for example, we boycott brandnames (Nike and Gap for example) to demonstrate our disapproval of sweat shops and child labour exploitation. I also think that buying from subculture markets is a way of encouraging local vendors and promoting local economy instead of buying into the whole capitalist consumerism 'thing'.

I've included cartoons and pictures boycotting certain stores that I thought would be not only entertaining but somewhat relevant to the article.

This image is of a boycott the Gap protest where the people said they would rather wear nothing than "The Gap".

http://www.commondreams.org/headlines02/images/0626-02.jpg

http://www.gearnosweat.com/frameset/swetshrt.gif

http://www.cartoonstock.com/newscartoons/cartoonists/mba/lowres/mban835l.jpg

Tuesday, February 12, 2008

The Everyday Life of Queer Trauma (Ann Cvetkovich)

Her investigation of trauma is an inquiry into how affective experience that falls outside of institutionalized or stable forms of identity or politics can form the basis for public culture. She basically wants to focus on how trauma makes its way into the everyday lives and the material details of experience.

The first thing I want to address is her discussion of trauma as a category of national, public culture. What kept playing into my mind as I was reading this section was 9/11. What I think is ‘funny’ is how the States took this tragic event as an excuse for what they were already doing overseas. Not only that but their excuse was irrelevant as they were targeting a different group than that of who they accuse of doing this. They have and still are fighting this battle and killing innocent people in the process, including their own soldiers. I think it just reinforced American national unity and identity, and ideas and assumptions about what they view as the ‘Other’.

Secondly, I found significant the idea that "public culture takes as a starting point the nation as a space of struggle, seeking to illuminate the forms of violence that are forgotten or covered over by the amnesiac powers of national culture, which is adept at using one trauma story to suppress another." In a different light, culture doesn’t see sexism as issue of trauma anymore but thinks it has been resolved and as a result has moved on to something else. Another example of this how ‘news worthy’ events;.we focus on them for a little while and then move on to what we consider more traumatic and rarely go back to those events and the aftermath. There is too much focus on the immediate.

I enjoyed the section about the 2.5 Minute Ride mostly because I could relate, having been to Auschwitz and Birkenau. Holocaust offers representations, which are the product of successful efforts to create a culture around a historical trauma. The author looks at juxtaposition of visiting the Holocaust. When I visited the site, it felt very surreal, almost made up in some areas. It has become a museum more than anything. It is only upon visiting the grounds of Birkenau that you ‘feel’ the trauma I think. I felt like the grounds were enough, I didn’t need to see the many objects collected and displayed through a window. Cvetkovich writes that "the challenge it addresses is how to make room for another kind of story in the face of the hyperrepresentation of the Holocaust and its saturation of the cultural landscape by a proliferation of horrific images."(23) As you can observe from the pictures, I also felt that I should not smile or show any sense of pleasure from being there. I had it in my head that I had to be in a particular mood when I was there and I this began from the moment I got in the train from Kracown. I’m not denying the true feelings that came of being there or the significant impact it had on my identity as a historian but I somehow had to make it worse in my head to do the place justice.

Finally, what I retained the most from this work is the need to push boundaries, not to be in the either or categories. This idea of everyday insidious trauma which Cvetkovich refers to, made me question the measurements of the impacts of trauma. It is a very difficult question to debate. Even after having spent some time on the issue in class, I still cannot decide if we can even begin to deconstruct trauma. How does one judge what is a "bigger" trauma than an other. There is a tendency to think that larger public traumas are more devastating than everyday life traumas. Truthfully, a build up of everyday trauma can be just a devastating, like the example we discussed about living with the repercussions of colonialism and how this oppression is part of the everyday. It affects how individuals shape their identities. Thus it is how you interpret your trauma and what it symbolises to you. We feel trauma and are not victims of it and it is a positive thing to feel what your life is like/your everyday and in the end make culture with it.

Wednesday, February 6, 2008

Who's Read Macho Sluts (Clare Whatling)

In some way I found this article quite interesting and relatable.

By drawing from examples of the book Who's Read Macho Sluts, Whatling focuses on the debate around consensual lesbian sadomasochism. One side says that it is a construction and effect of patriarchy and that it reproduces and condones many power imbalances while the other argues that it is more an imitatation of patriarchal relations as parody and occasionally deconstructs them.

She also speaks of "the notion of moral purity of one group of women (vanilla) is problematic where a hierarchy of values is set up in our society which makes of one practice the norm and of the rest scales of deviance from." (419)I have issues with this idea that everything that falls out of the norms of sexual behaviour is wrong. What is considered normative in sex is usually man and woman, man experiencing pleasure, woman perhaps (if she’s lucky), woman being passive, man being aggressive; this is not always the case obviously but it is the general idea. Or even the assumption that sex between woman and man is out of love and is consensual. Unfortunately, that is not always the case.

What I found most interesting in this piece is her discussion on women's relation to violence and sadism as it has been theorized in feminism. Feminism has worked with the idea of violence as the prerogative of men and as the abuse of women. This way of thinking is to Whatling a fundamental one to a certain moment within feminism but argues that this focus on men and violence has ignored other power relations. I think that we have to recognise the power of women in relationships and sex, women are not only victims of abuse but perpetrators of it as well. This ties in to the what Whatling says about what we think is the non-existence of female sexual sadism but that in reality it is rendered invisible by its cultural suppression. "Women are not believed to be sadistic because they are not seen to be, at least if they wish to remain “womanly"."(421) What is the definition of "womanly"? I see this attitude as a refusal or denial on the part of feminism that there is a possibility that patriarchy is not to blame in this case. Since patriarchy has held most of the blame for so long, it seems that feminism might find it difficult to part from it.

The author is also arguing for a way of reading "which allows women access to a multiciplicity of subject positions and thus multiple viewing-pleasures, whereas beforehand only one was theorized, namely the masculine."(423) This made me reflect on the fact that we very often or almost always hear or are forced to hear the stories of male fantasies but very seldom hear of women’s fantasies. It's always about a what men desire (ie: threesome, woman/woman) and women having to hear about it or made to feel guilty about not engaging in these activities to fulfill fantasies. I found it interesting when she gave the example of a lesbian woman giving fellatio to a man and experiencing pleasure as her own. The idea that she’s not doing it because she feels obligated to do so like in some cases of heterosexual relations where a woman is performing the act as a way to satisfy man's desire and/or respond to norms of foreplay.

Another crucial idea in this text, in my opinion, is that feminism allows for fantasies of "Amazons and vampire to our heart’s desire, as soon as fantasy enters the realm of the explicitly sexual, a totally other standard pertains and we are required to police our thoughts for signs of political reaction."(423) It also involves issues of guilt from these fantasies. I always wondered that if one like myself who has a feminist identity fantasises about events or actions that in reality are against what whe are fighting for or believe in, should feel guilty. Whatling argues that we cannot assume that "although fantasy isn’t real, it is culpable because it imitates actual events, in other words, that someone’s fantasy is someone else’s reality."(425) We have to remind ourselves that there is no active relation to what torture means in reality. There needs to be exploration of the pyschological relation between fantasy and desire. At the same time, Whatling explains that desire does not have to be confined to one’s active sexual preference, that sexual identity does not necessarily have to do with the one you take on in your fantasy, which in the end, allows for more freedom of self identification. It allows for choices basically.

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

Returning to Manderley (Alison Light) / Romance and the Work of Fantasy (Janice Radway)

In this article the author focuses on Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca which is the late 1930s story of an orphan girl who marries an aristocratic widower and has got everthing a romance needs and more. First, Light presents the Left political view that romance novels reinforce the role of the submissive woman only to criticise it by arguing that women aren’t so easily manipulated and that readers are more complex than that. She argues that we should not be afraid of pleasure that comes from reading such literatures and she sees fictions as « restatements of realities. » I too, once thought that romance readers were desperate housewives who were trying to fill a void in their lives. I thought of romance novels as cheesy and simply degrading women by promoting the idea of an eroticized woman being swept off her feet or even "rescued" by a strong, tall, dark and handsome man. Although I do not want to generalize, we have to be honest with ourselves by saying that at some point we have imagined such a fantasy, searching for that self that could possibly experience this "romance". Here is the problem though: romance novels (that I know of) are usually aimed at heterosexual women. However, Light does specify that the « self » that comes of reading romance equals the norms of female heterosexuality. So in a subtle way, she acknowledges that these texts are not representative of homosexual experience. In her conclusion, Light makes the point that women who read romance fictions are, « as much a measure of their deep dissatisfaction with heterosexual options as of any desire to be fully identified with the submissive versions of femininity the texts endorse » and urges feminists to analyse romance and its reception as symptomatic instead of reflective.

Romance and the Work of Fantasy – Struggles over Feminine Sexuality and Subjectivity at Century’s End (Janice Radway)

Janice Radway seeks to « review the nature of the struggles that have been conducted at this site (that of the struggle for feminine subjectivity and sexuality) and to show that just as feminist discourse about the romance has changed dramatically in a short time, so too has the romance changed as writers have resisted the efforts of the publishing industry to fix the form in the hope of generating predictable profits. » (396) She praises the accomplishments of romance writers by stating that they have showed an increased confidence in claiming female sexuality and have imagined a female subjectivity to support it.

Radway offers an overview of romance of the early 1960s and presents two critical views of them: 1) romances as a threat to patriarchal culture due to the sexual revolution and, 2)romance seen as a backlash against the women’s movement. Her response to this is that « policing was the real work enacted by leftists and early feminists critiques of romances and their readers. »(397) She thinks that by criticizing women they were reinforcing their authority on them and dictating what they « ought » to be doing instead of reading romance novels. I completely agree with this. It seems as though, still today, men or women who are still embedded within the patriarchal views of « woman » are often threatened by women stepping out of normative female identities. God forbid, a woman should think about sexual pleasure or go off in a world of fantasy. It seems that men are the only ones allowed to do this with pornography. For men to do this is often seen an natural, like an innate behaviour or desire. In fact, one could think that a man who does not engage in such activities or dreams does not fall into the heterosexual male norm.

Radway reinforces the idea that the fantasy of the romance is closely connected with the social and material conditions of women’s lives in a patriarchal culture. Later in the piece she offers a brief history of the evolution of romance novels and publishing companies while arguing that feminism made its way into romances through the career aspirations of the middle-class writers of the genre. What we are left to consider is that fantasies are offerings of different versions of female sexuality and different subject positions for readers to experience and try. I now see it as perhaps a safe place for women to experience their sexuality before thinking or actually engaging in certain situations in their reality. Some of them may or may not or probably never experience these outside of the romance novel but can certainly take full advantage of this place to explore their inner self.

Saturday, January 26, 2008

Eating the Other (hooks) / Soft-soaping empire (McClintock)/ Devouring theory (Kenway & Buller)

LOOKING INTO THE MIRROR, THE BLACK WOMAN ASKED, "MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL, WHO'S THE FINEST OF THEM ALL?" THE MIRROR SAYS, "SNOW WHITE, YOU BLACK BITCH, AND DON'T YOU FORGET IT!!!"

Fig. 3 Carrie Mae Weems, ‘Mirror/Mirror’

hooks' Eating the Other argues that that difference and imperial nostalgia of the White Western male (for the most part) for dominance over the Other is enacted through cultural appropriation. This idea entails that the White supremacist male has a desire and attraction towards what is considered exotic and different because it presents an opportunity to step out of conventional white mainstream culture. Like hooks says in the first paragraph of her article she states that "within commodity culture, ethnicity becomes spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is mainstream white culture."(21)More importantly, only white males are permitted to express this fascination. So bodies become a terrain of neo-imperialism we could say and white supremacists take from those bodies to claim that they are no longer racists, so the Other is commodified in other words. We are using the "Other" for our own redemption and benefit. She uses the idea of cultural commodities to demonstrate the importance of space and place in identity and cultural politics. This whole process is then amplified through media to the point that it becomes acceptable to buy into it.

I do not know if I was shocked by the ideas hooks presented because I was unaware of this phenomenon if you want to call it so, of if I had just never chosen to look at it that way. I would like to think that I was unaware of it but the fact that I am highly exposed to consumer media suggests that I chose not to see through it. It's interesting to think that although we are very aware of the existence of racism, our society still chooses to propagate in more "subtle" way through media ads and consumerism and this for its own benefit most of the time. One of the ideas that I recognized was when hooks writes about the American Dream and that "the acknowledge Other must assume recognizable forms."(26) It made me reflect on the fact that the Other's cultural identity is perhaps not their own but something that mainstream white culture has created. For example, let's think about the identities we associate with certain races and ethnicities: docility, oversexualised, violent, submissive, pure, evil. hooks criticised Torgovnick's work because of "her refusal to recognize how deeply the idea of the "primitive" is entrenched in the psyches of everyday people, shaping contemporary racist stereotypes, perpetuating racism."(32) One that that came to mind immediately was this idea that I had before I moved to a major city where cultural diversity was so prominent. It was the idea that I had to beware of Black men walking on the street late at night, to fear that they might attack or rape me. How did this idea became part of me? I knew and I know I am not a racist yet this idea was one that had been part of my upbringing and exposure to ads, movies and television shows. Is it possible to completely erase those ideas?

Another important point of interest that I could relate with was when hooks describes fashion catalogue ads that exoticise the Other. It reminded of a trend that has developped in the last few years. It seems going to Africa has become trendy within the dominant culture. Personnally, I have many friends who have partaken into this trend. Some for school purposes and work but many for the simple fact that it has become a hot spot for travels. Why is that? Is it because it's different, seen as exotic or because we want to have a bit of the Other as hooks says. Take people that go down south during the winter and come back with braided/beaded hair. I never understood that. Those people wouldn't normally do that to their hair here in Canada so is it that being in an "exotic" country that allows to express your desire or your "taste" for the Other?

Overall, hooks article advises us that acknowledging and exploring "racial diffrence can be pleasurable (and) represents a breaktrough and a challenge to white supremacy, to various systems of domination."(39) However, I think that we have a very long way to go. There needs to be a complete overhaul of consumer culture and an awareness of how we have created a neo-imperialist society in consuming the Other.

The article was a good historical overview of how those who have been "othered" have been used as commodities during imperial times and have perpetuated what is going on today.

I was completely shocked at the nature of packaging and advertisements for the soap, how racist and obvious they were. It made me think of how powerful advertisement was and is even more so today in creating this idea of the other and how it encourages the furthering of racism and sexism.

Interesting also is the link that was made between racial commodities and domestic commodities. As the video "Advertising and the end of the world" portrayed advertising has colonised culture. Although today it might not look or seem as explicit as what the soap advertisement were racism and female objectification are still propagated through these means of communication. What they were doing during the 19th century was to colonise the other which were Blacks and women, today they are colonizing all members of society the same way, through fantasy which is what is desired at that moment in time. Through technology it has become easier to do.

This chapter argues that the market and information and communication media together hold powerful and privileged position in today’s culture, society and economy which I think has been facilitated by the wide array of technoology. Consumption is now recognised as defining characteristic of the lifestyle of the western world and as a result we could even say that consumer culture is now inside our identities.

The chapter is about historical and theory background to book. It begins with an overview of key moments in consumer media-culture history and then offers an outline of different ways in which social and cultural commentators have theorised consumer media culture. The purpose of the first part is to identify key changes over time in consumer media culture in the so-called developed countries of West.

They also speak of the strong tendency in consumer culture to erase history. I think that as a society we find it so easy to dismiss the pass, especially younger generations. They do not see the importance of holding on to the past, even the future seems too distant and irrelevant unless it has to do with tomorrow, a week or two from now. Consumerism and its products are changing so often that I think it becomes trivial to hold on to anything other than the present. The authors argue that consumer-media culture changes constantly and is becoming more complex to sustain itself and that we need to "make use of newer foundations and theories in order to actually understand the changes and complexities." ( )They identify three main points in literature on consumer culture:

1)production of consumption approach

2) the modes of consumption approach

3) apparoach that emphasizes the consumption of dreams, images and pleasures

I also appreciated their definition of the central features of consumer culture as "the availability of an extensive range of commodities, goods and experience which are to be consumed, maintained, planned and dreamt about by the general population."( )Just like the video Advertising and the End of the World explains, advertising portrays how people are dreaming, not acting. So what are we really doing? Are we wasting our time dreaming about what could be or of what would make us happy. It is interesting to think of how much time and money we are wasting away in being "consumed" by the desire to gain material goods that we think will make us better and creat a respectable identity within society. When I was watching the video, all I could think about was how much money we waste on making those advertisements and consuming as a result of those advertisements. While we are doing this, there are people that are living without any possession or living below the poverty mark. It's unbelievable to think that we choose to spend money on useless promotion.

Friday, January 25, 2008

Feminism and Cultural Studies (Shiach)

She also describes cultural studies as a source of change which can sometimes be threatening. In a sense, Women's Studies is also a place where change comes from and which is very often seen as threatening to those adhering to conservative views. Thus it makes complete sense that Shiach speaks of cultural studies in relations to feminism. In fact her main purpose in writing this introduction and chapters that make up the book is to recognize the force and variety of work that has been done by feminist critics working in the realm of cultural studies in the last twenty years.

She believes that the lack of recognition is that feminist foundations have never been strong enough to really engage with the theoritical models that cultural studies draws upon. (4) I am unsure if this is true however. I am not familiar enough (yet) with the relationship of feminism with cultural studies nor have a strong background in cultural studies to engage in this debate. My initial response would be that feminism is in fact strong enough but does not feel that it is. Because it more often than not has to prove itself in some way or another, feminism might have an inferiority complex and as a result does not feel that its foundation is strong enough. I think that as I go along with the readings, this discussion will be elaborated on in future posts.

Feminism, Postmodernism and the "Real Me" (McRobbie)

To answer her main question the author explores the split agenda of postmodernism and postcolonialism in understanding contemporary society. She also asks us as intellectuals and feminists to question our intellectual place in postmodernity and postcolonialism and in feminist politics. The ideas of living with and embracing difference, and the construction of the social self through postmodernism are explored. McRobbie also recognizes that strength of feminism to go across and negotiate boundaries is what is needed to redefine the term "woman". When she speaks of this, I really enjoyed what she said about exploring boundaries by going back to them.

"How might the continual process of putting oneself together be transformed to produce the empowerement of subordinate and social categories...inventing the self rather than endlessly searching for the self (...)" (72) This quote was by far my favorite in this article. My first thought was of the saying that so many people speak,."I'm trying to find myself". It is like our "self" is suppose to be out there somewhere for us to find when in reality we should be creating ourselves. Why conform to the norms and be influenced by mainstream culture when you can create your own individual self? On a more personal note, up until a few years ago, I felt that I could never be truly happy because there was always something new coming out that meant that I wasn't up to par with what society expected of a twenty something year old. I just gave up at some point; I could not keep up. I could not "find myself" through conformity so I decided to "create" myself and will continue to do so as my life progresses. There is no one true self, life experiences will shape it and bring me to change and reflexion.

The same thing is implied for feminism and Women's Studies. There is no one true or unique identity. Like the author mentions it is an "amalgam of fragemented identities" and we should not try to label or give it a specific definition for it is ever changing. I am convinced that feminism needs to constantly question itself about whom it is speaking to, of, or for.